ogmini - Exploration of DFIR

Having fun while learning about and pivoting into the world of DFIR.

About Blog Posts by Tags Research Talks/Presentations GitHub RSS

David Cowen Sunday Funday Challenge - SSH Artifacts in Windows 11

by ogmini

David Cowen has posted his weekly Sunday Funday challenge at his blog and it is related to his previous challenge on SSH Artifacts in Linux systems. I had posted that looking at SSH Artifacts in Windows would be a natural extension and here we are.

This week is a bit crazy, so I’ll be working on this over a few days and doing small updates. This post will compile all the work for submission.

Challenge

Test what artifacts are left behind from SSHing into a Windows 11 or 10 system using the native SSH server. Bonus points for tunnels.

Test Setup

I am performing testing using three Hyper-V VMs

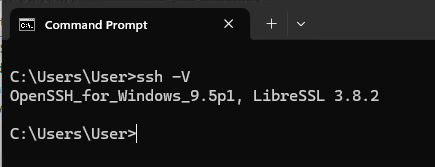

Windows 11 Client

Windows 11 Pro 24H2 26100.3476

Default installation

OpenSSH_for_Windows_9.5p1, LibreSSL 3.8.2

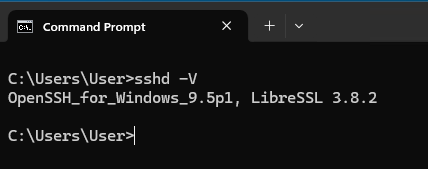

Windows 11 Server

Windows 11 Pro 24H2 26100.3476

Default installation w/SSH Server Feature

OpenSSH_for_Windows_9.5p1, LibreSSL 3.8.2

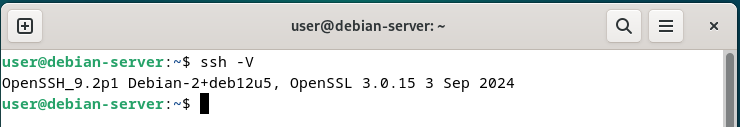

Debian-Server

Debian GNU/Linux 12

Default installation w/SSH Server

OpenSSH_9.2p1 Debian-2+deb12u5, OpenSSL 3.0.15 3 Sep 2024

SSH Testing Steps

- Open SSH connection from Client to Debian-Server using “standard” username/password authentication

- Explore for artifacts

- Open SSH connection from Client to Windows-Server using “standard” username/password authentication

- Explore for artifacts

- Add/Enable SSH Public Key to Windows-Server

- Open SSH connection from Client to Windows-Server using the private key

- Explore for artifacts

SSH Tunnel Testing Steps

- Open Local Port Forwarding from Client to Windows-Server using the private key

- Explore for artifacts

Artifact Theories

I believe the artifacts will be similar to those found in Linux since both use OpenSSH. The paths will differ, but I expect to see a known_hosts file along with any public and private keys. Unlike Linux, Windows does not use systemd for logging; instead, it collects event logs which can be viewed in Event Viewer. It will be interesting to compare them and see if they both log similar information.

Exploring for Artifacts

I’ll be using the built in Windows Event Viewer to search for logs and Process Monitor to look for any registry keys or files that have been touched during testing.

SSH Test Results

Standard Username/Password Authentication to Debian OpenSSH Server

As expected and similarly to the testing we did on Linux, the client leaves behind very few artifacts. We don’t even have the .bash_history to fall back on. Windows Command Prompt doesn’t keep a history across sessions unless you delve into memory forensics in the moment.

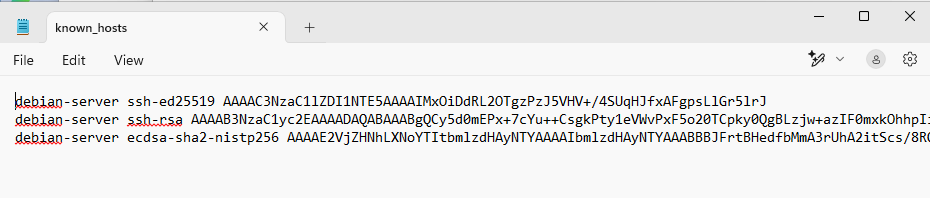

known_hosts

The only artifact we have is the known_hosts file which is located at %userprofile%\.ssh. Unlike Debian which hashes the hostname and IP by default, Windows does not so we can get more information from the file.

Event Viewer - Debian

On the client Windows 11 machine, there are no relevant logs to be found in Event Viewer.

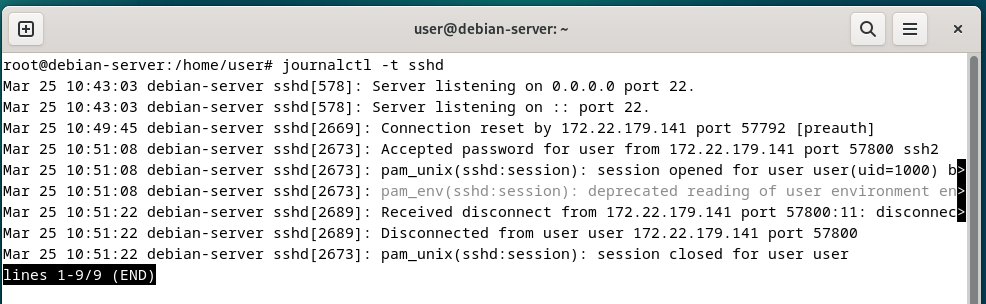

systemd

On the Debian machine, we again see logs relating the connection of the user. Nothing that specifically identifies the connecting machine as Windows 11.

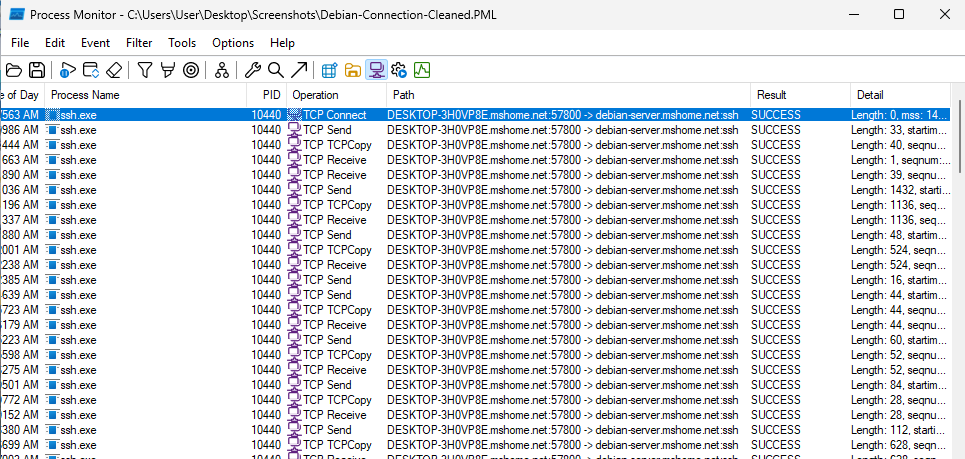

Active Connections - Debian

Using Process Monitor on the client Windows 11 Machine, we can see network traffic related to the SSH connection. This could also be done using net stat and other tools.

Standard Username/Password Authentication to Windows OpenSSH Server

The artifacts on the client Windows 11 machine are the same as when connecting to the Debian machine.

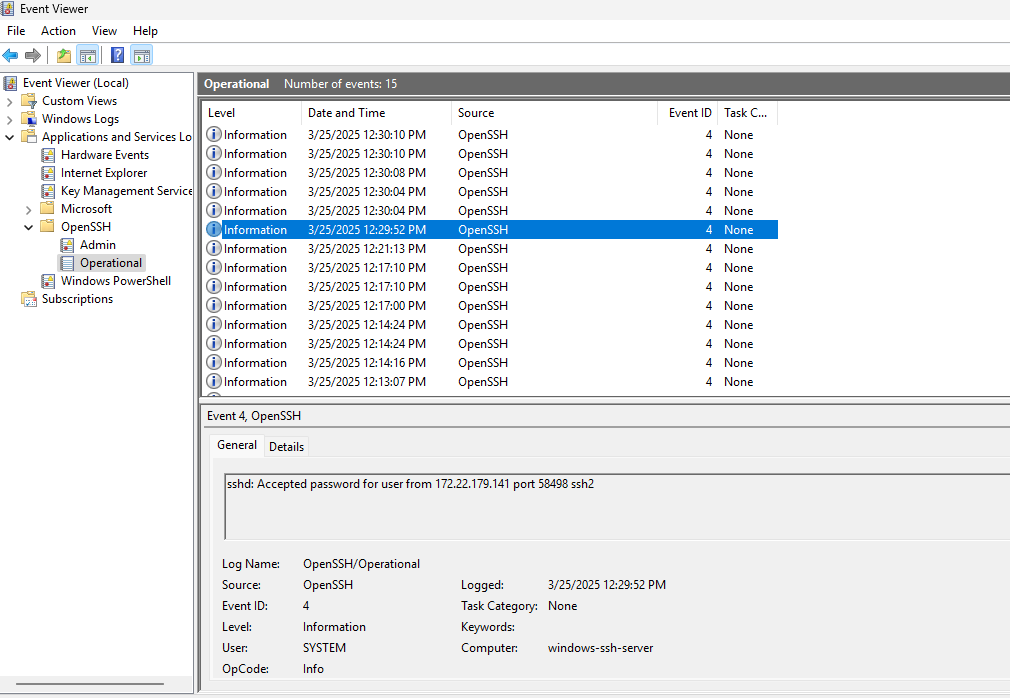

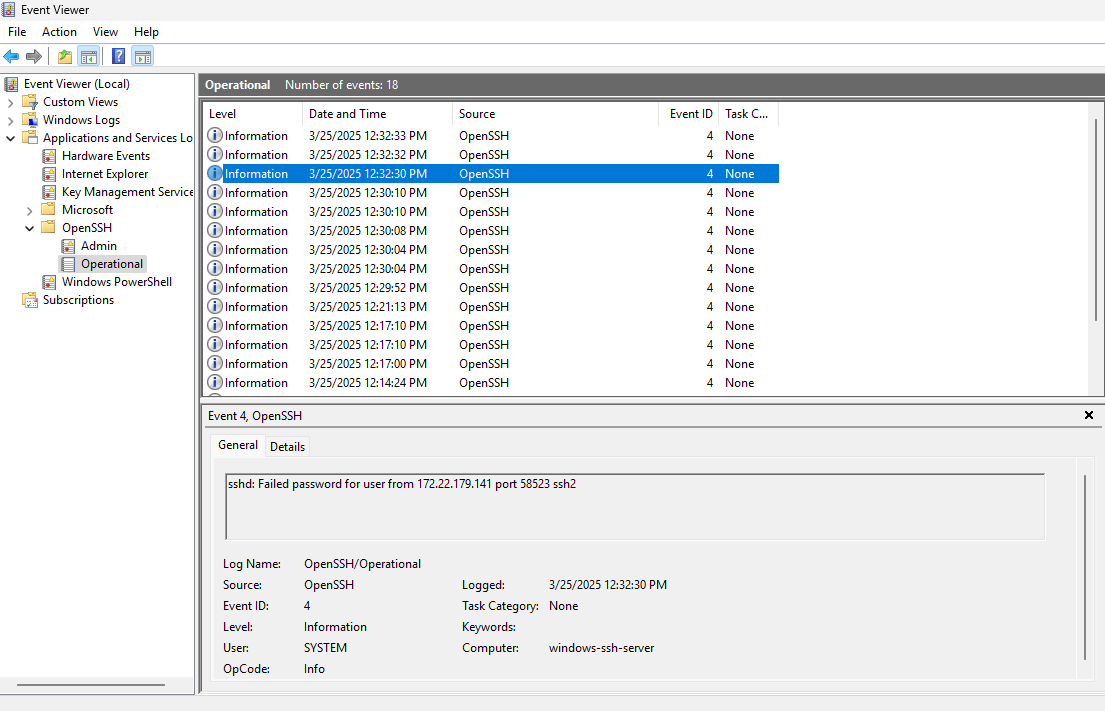

Event Viewer - Windows

On the server Windows 11 machine, there are relevant logs to be found in the Event Viewer.

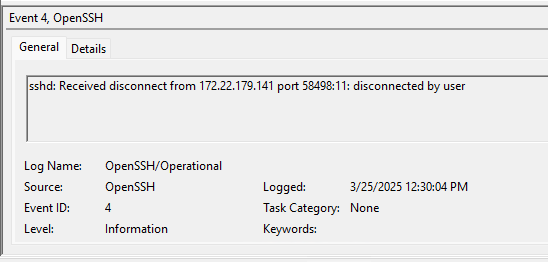

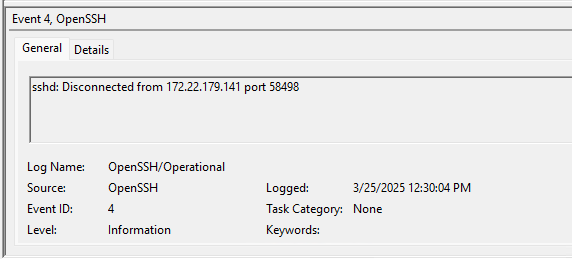

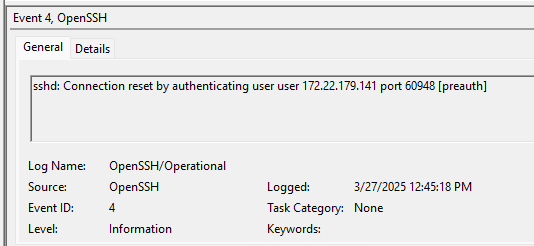

Under Applications and Services Logs -> OpenSSH -> Operational we find log entries related:

- Password attempts

- Disconnections

- Connection Resets - These result from the user Ctrl-C’ing before a connection is made

Success

Failure

Disconnect

Connection Reset

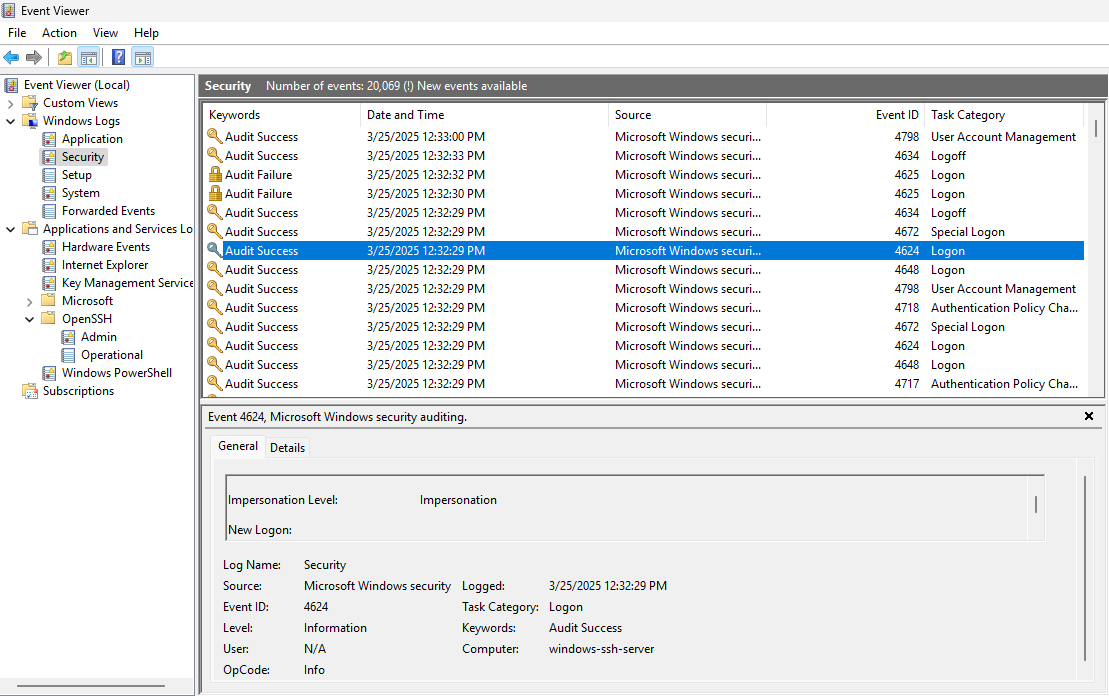

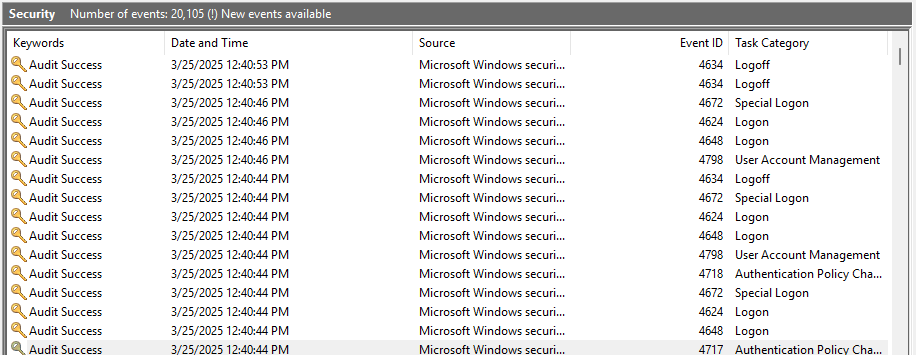

The next logs are found under Windows Logs -> Security and some will start to look familiar as being related to the normal user logon process.

We can see the following EventIDs are related to a user connecting to the machine:

- 4717

- 4648

- 4624

- 4672

- 4718

- 4798

- 4634

What is interesting is that the account is initially logged in with a temporary user account named “sshd_4568” in this case. I’m unsure how the numbers at the end are determined. This is followed by the system assigning it impersonation privileges in EventID 4672. Next the actual user is logged on. At logoff, we see both the “sshd_4568” and the actual user account Logoff with EventID 4634.

Detailed Analysis of Windows Event Logs

Logon IDs

In the log analysis below, we will see the following Logon IDs:

- 0x3E7

- 0x44C61B

- 0x44C8A8

- 0x44C907

Successful Login

Pay special attention to the Logon IDs which are listed right after the EventID. Also note that “WINDOWS-SSH-SER$” is the shortened name of the server Windows 11 machine.

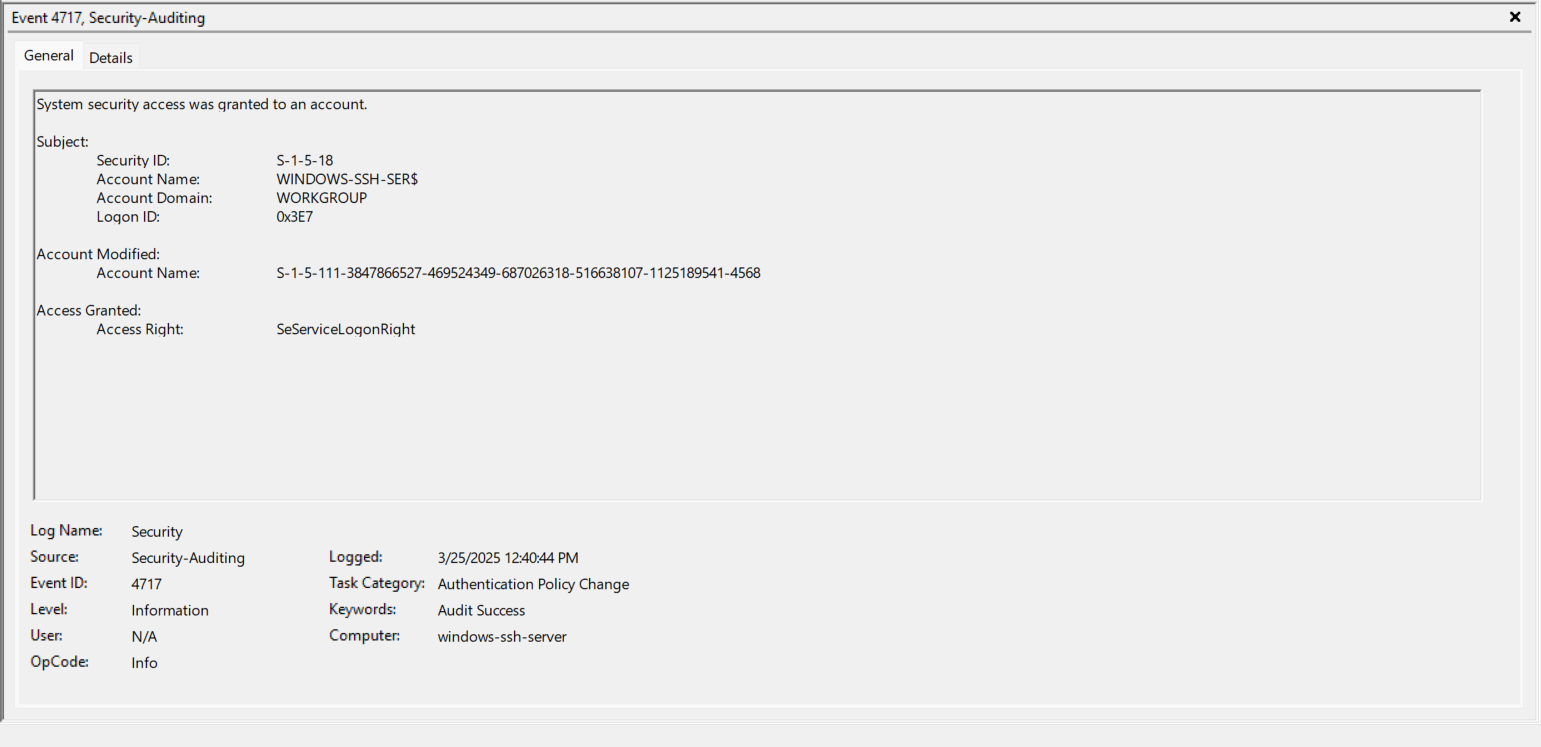

- EventID 4717 (0x3E7) - WINDOWS-SSH-SER$ is given the SeServiceLogonRight. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4717

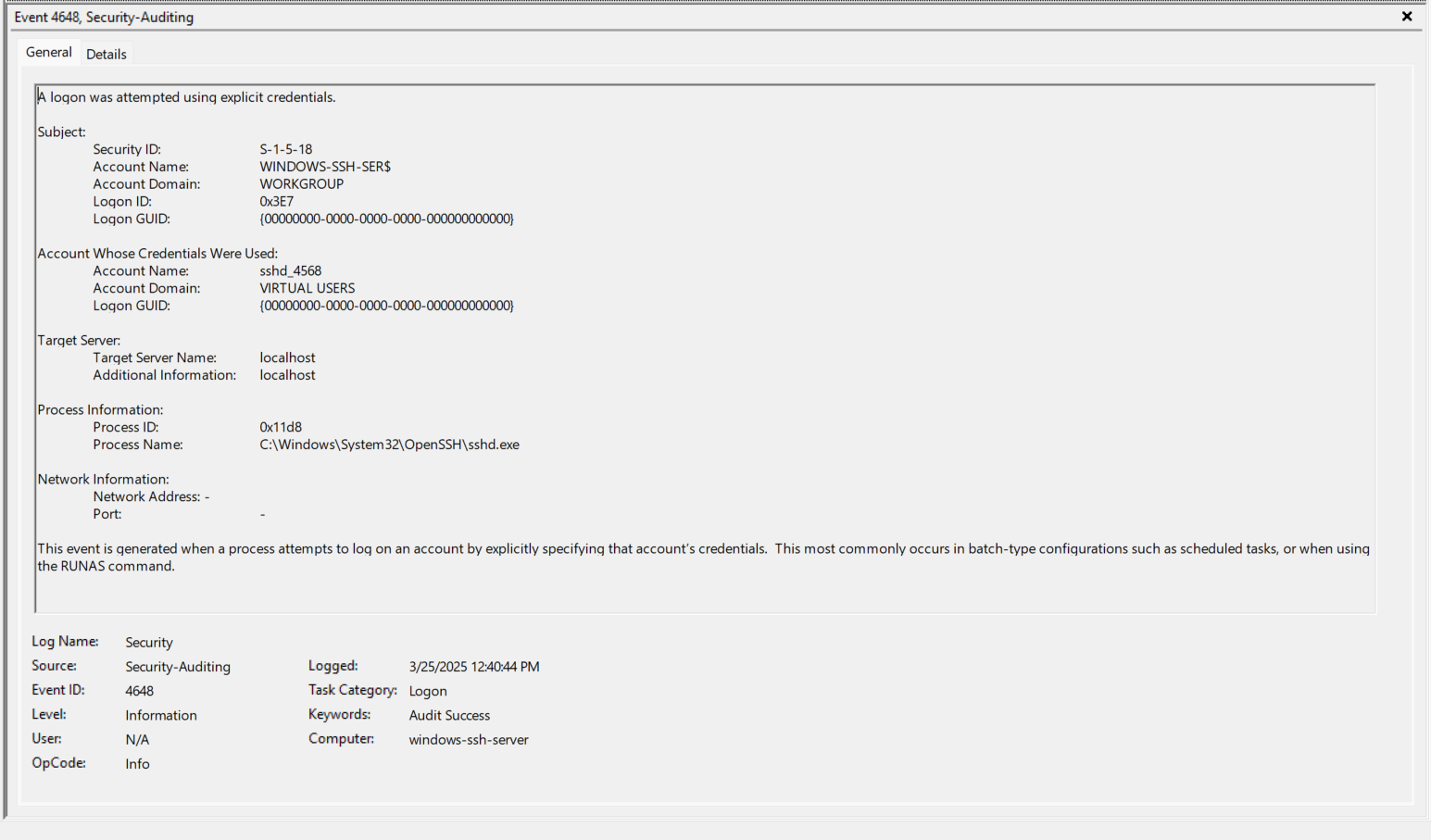

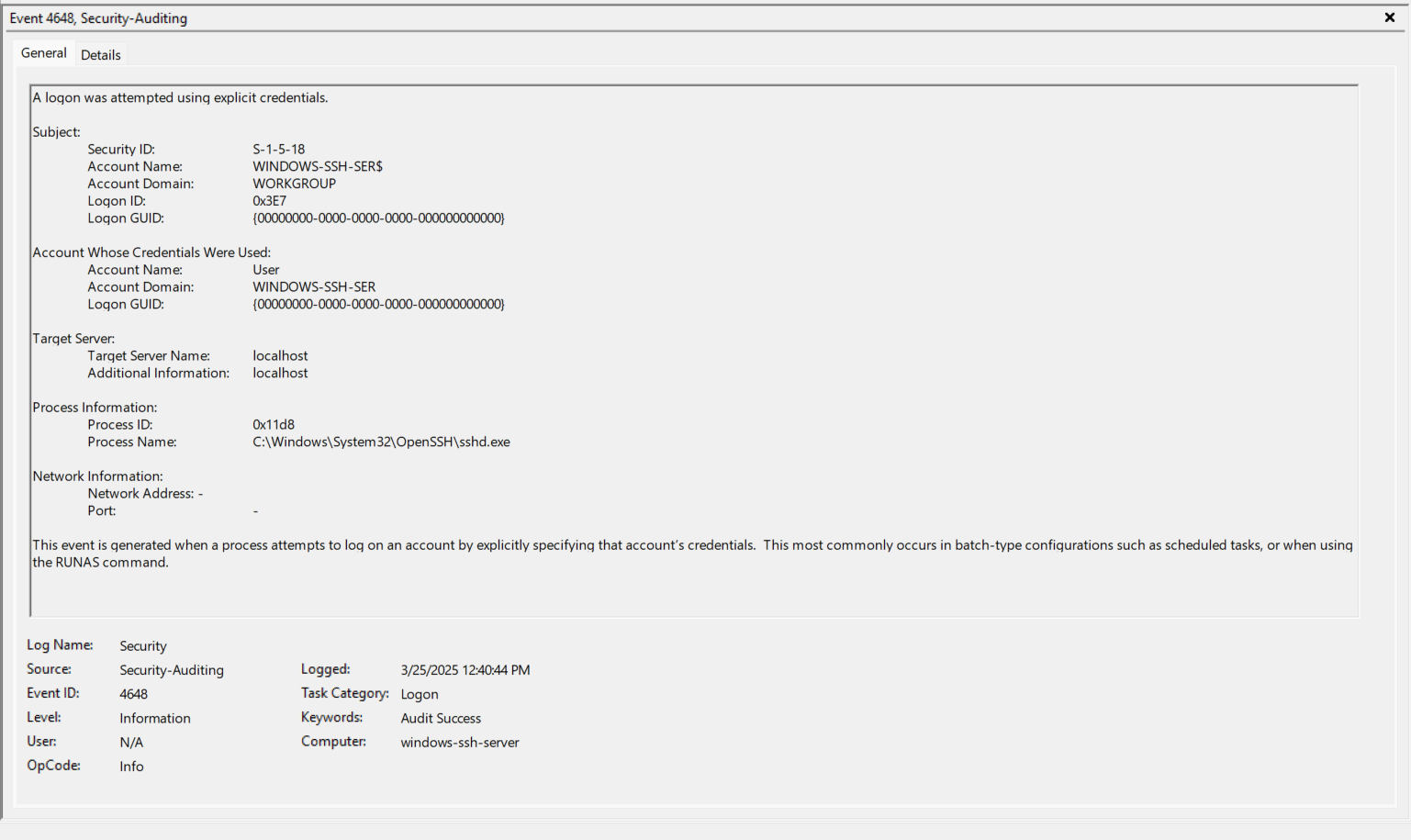

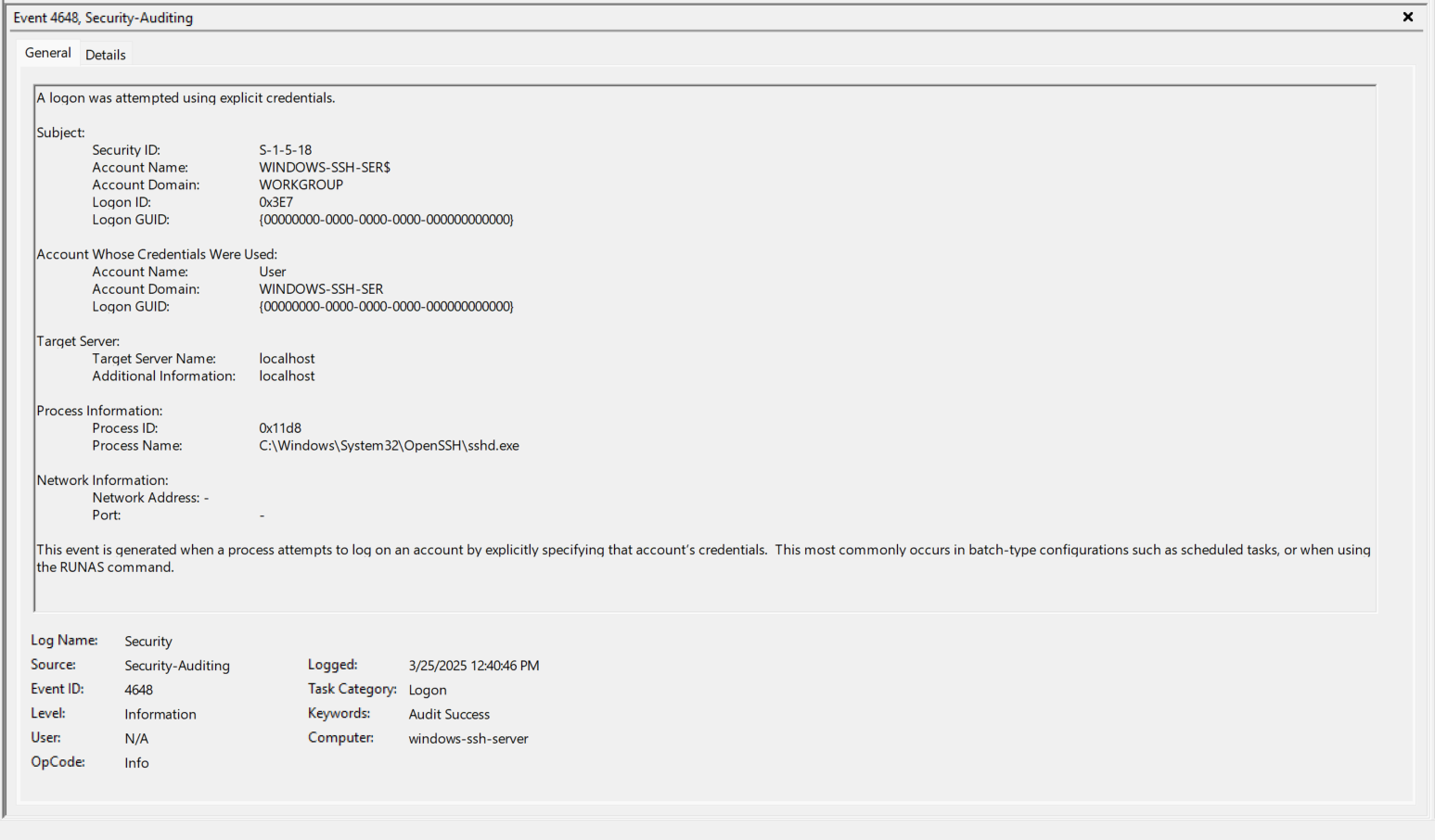

- EventID 4648 (0x3E7) - The sshd.exe process now logs on (RUNAS) as the Account “sshd_4568”. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4648

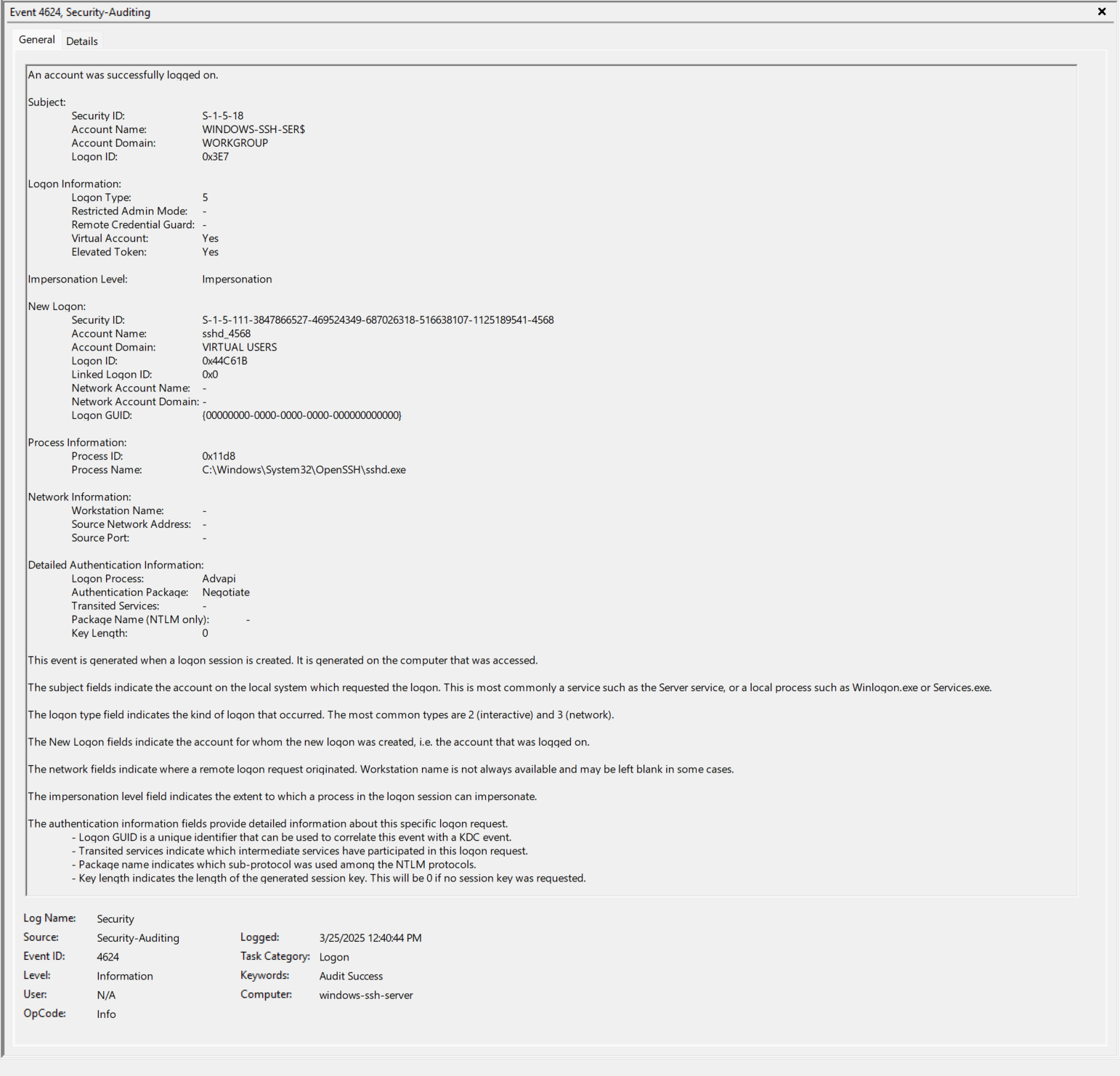

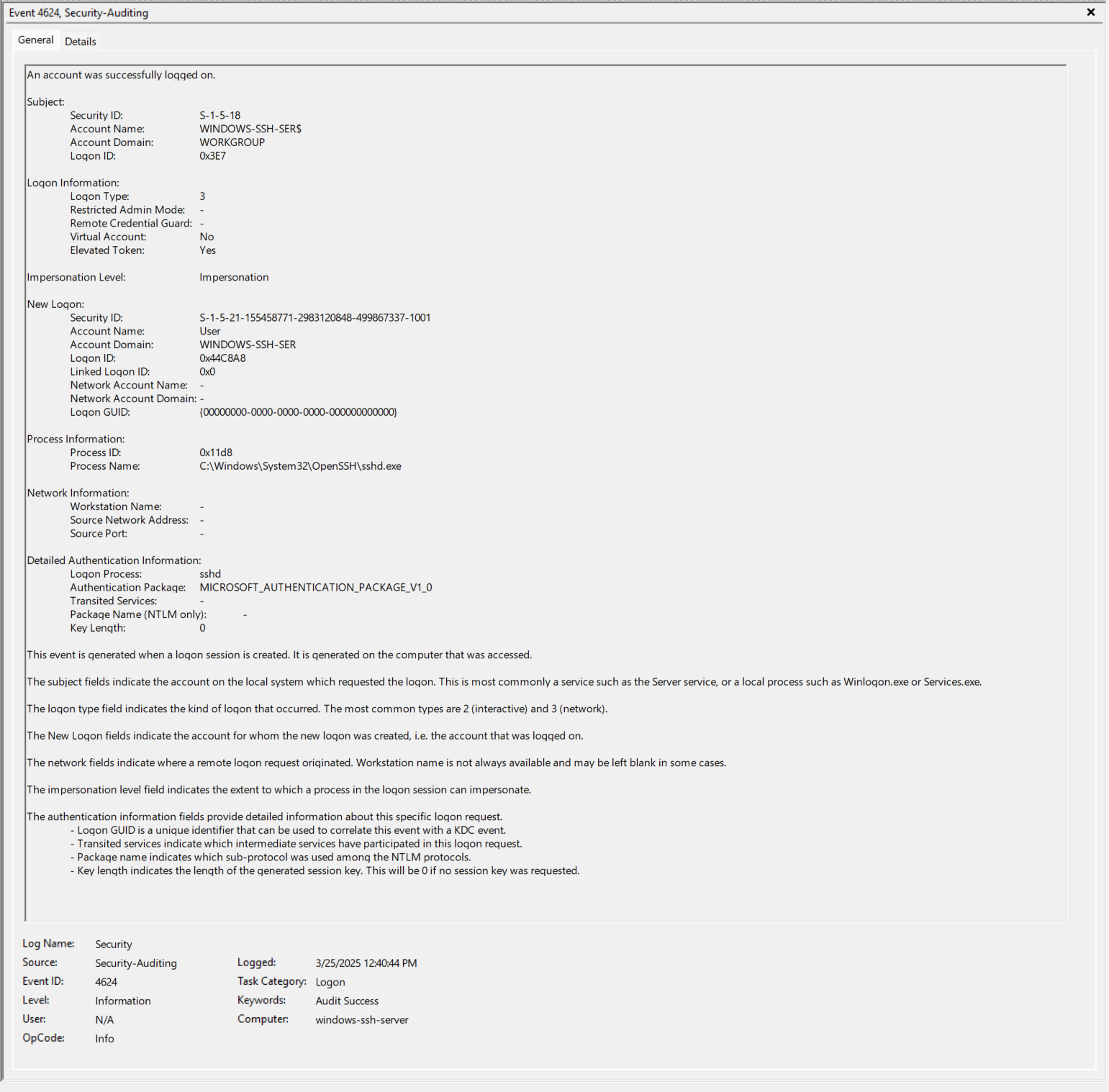

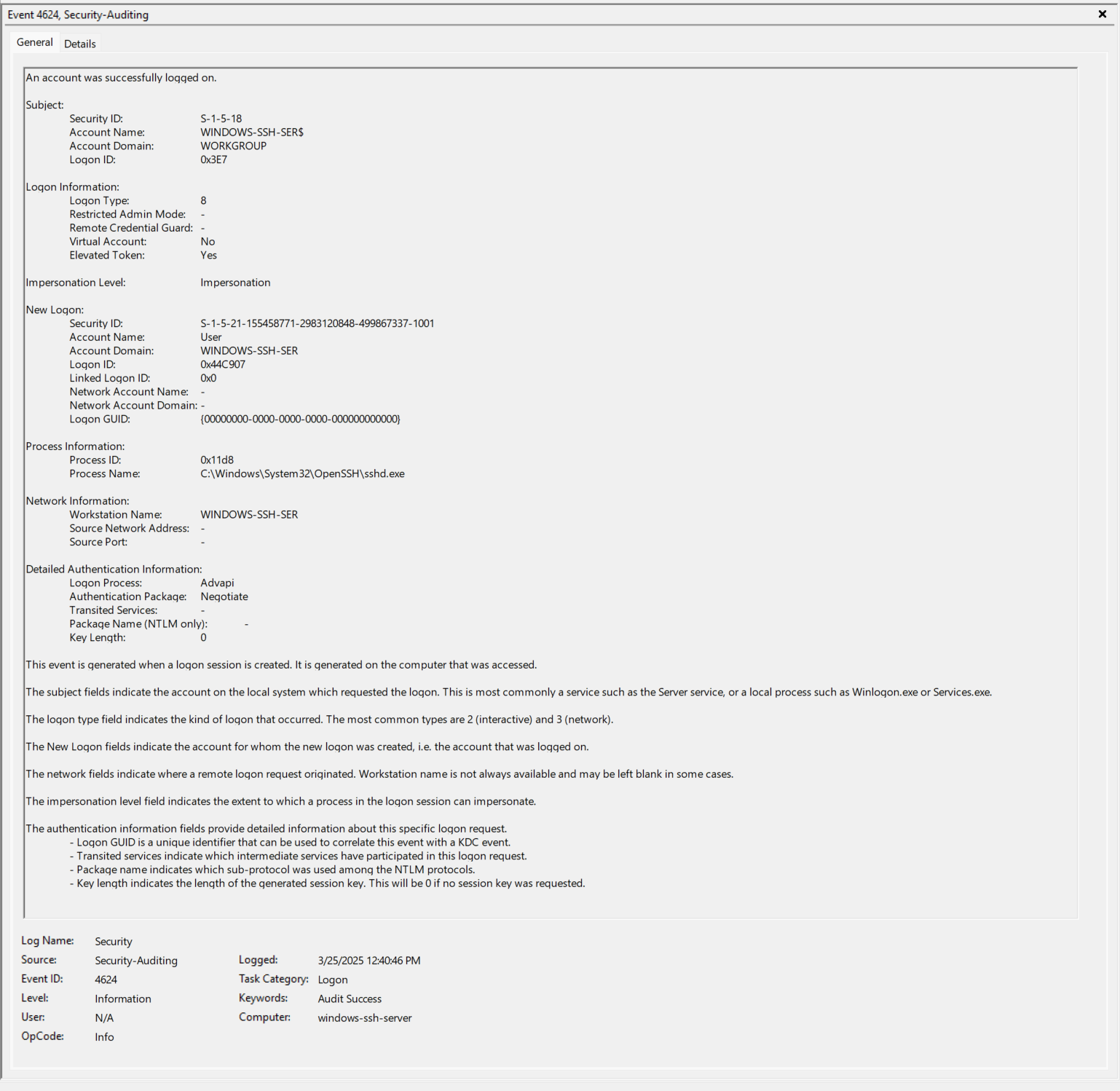

- EventID 4624 (0x3E7) - Take note of the Logon Type, Virtual Account, and Elevated Token. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4624

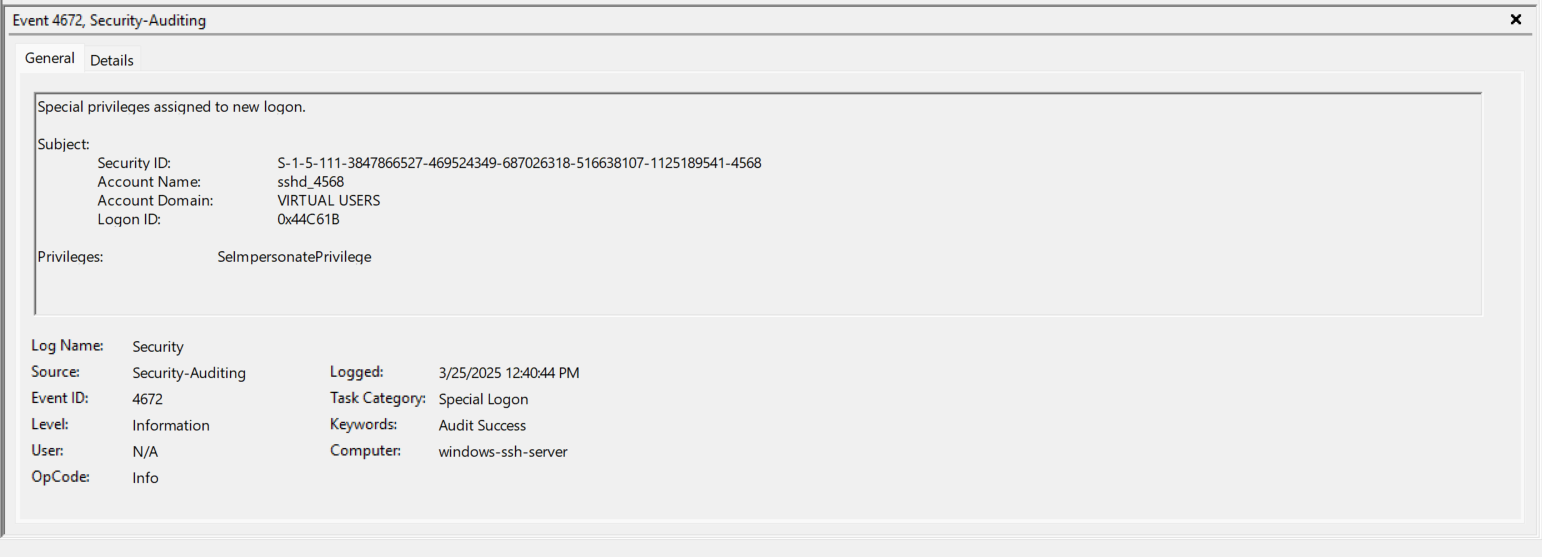

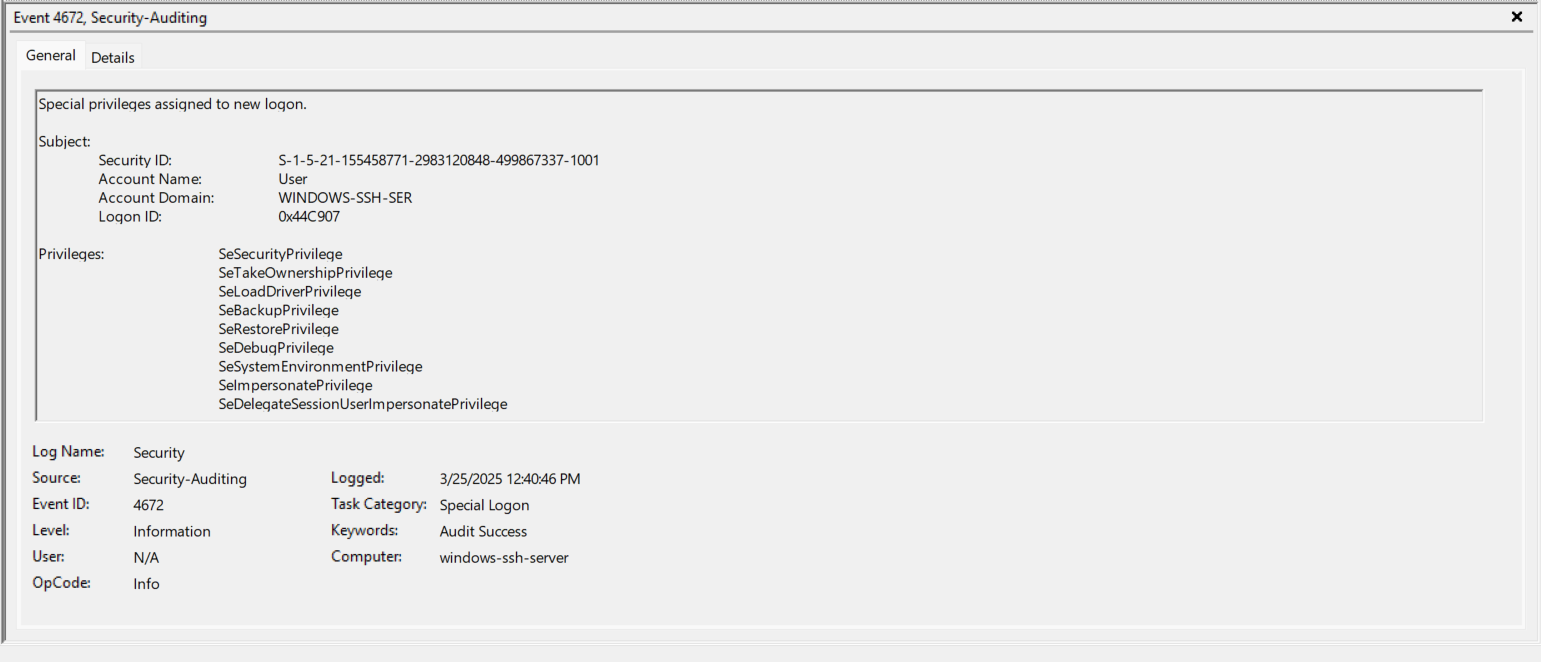

- EventID 4672 (0x44C61B) - “sshd_4568” is given the SeImpersonatePrivilege. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4672

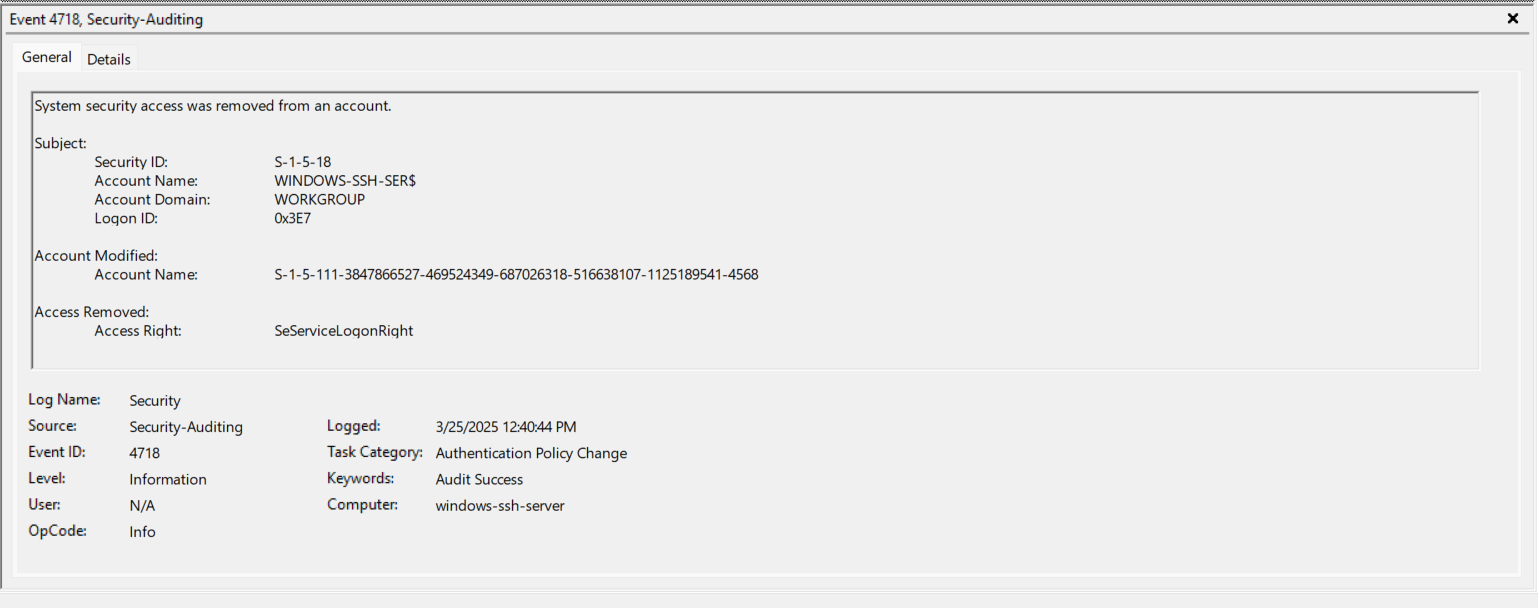

- EventID 4718 (0x3E7) - WINDOWS-SSH-SER$ has the seServiceLogonRight removed. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4718

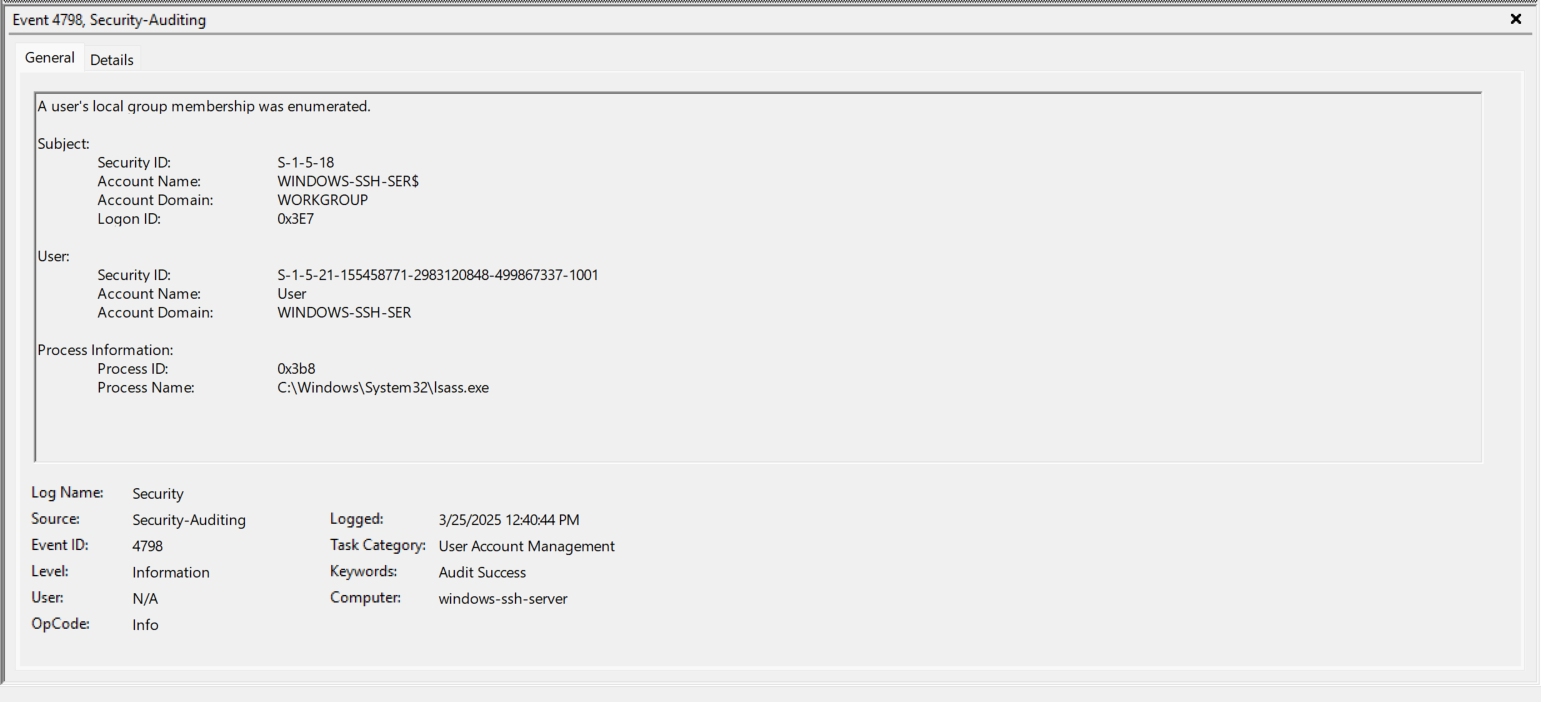

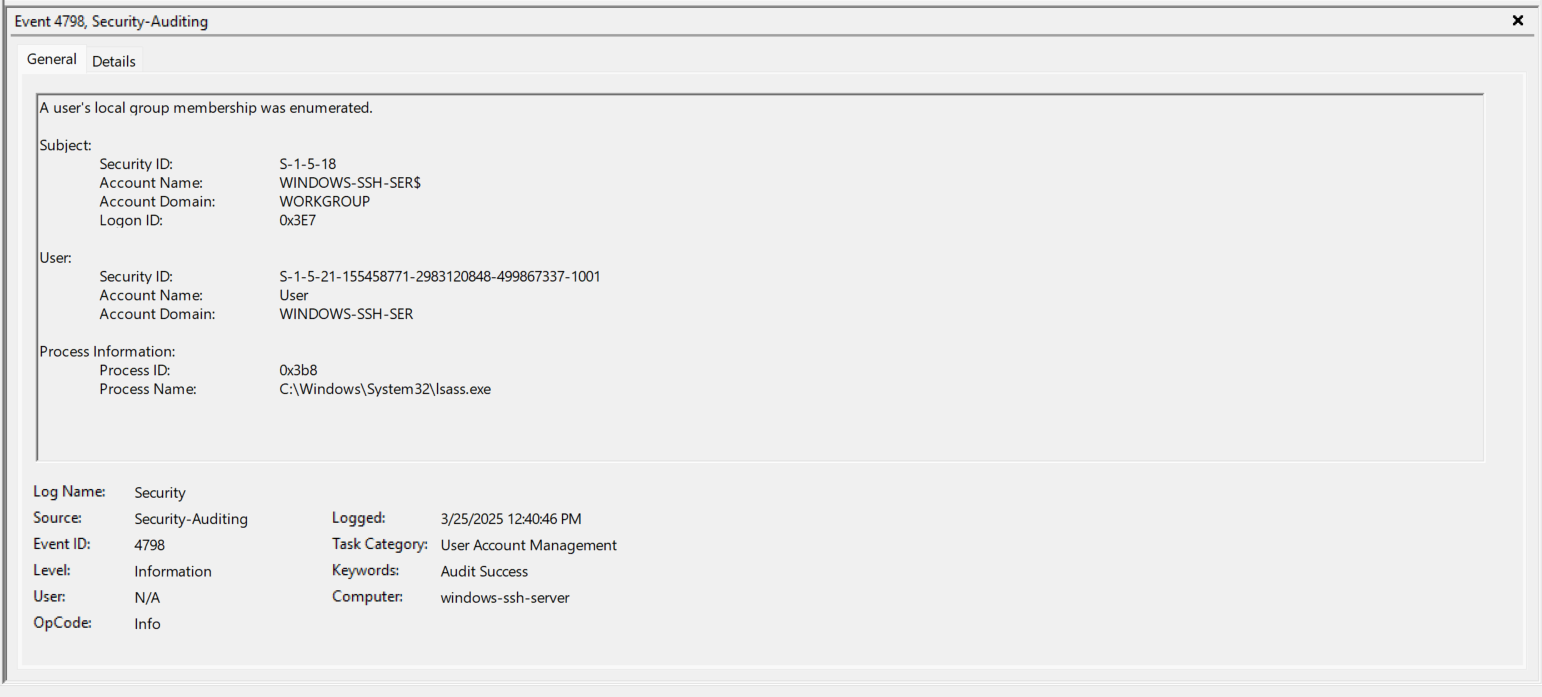

- EventID 4798 (0x3E7) - Enumerates local groups for the User we’ved logged in as. Again, I chose a bad username of “User” for testing purposes. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4798

- EventID 4648 (0x3E7) - The sshd.exe process now logs on (RUNAS) as the Account “User”.

- EventID 4624 (0x3E7) - Take note of the Logon Type, Virtual Account, and Elevated Token.

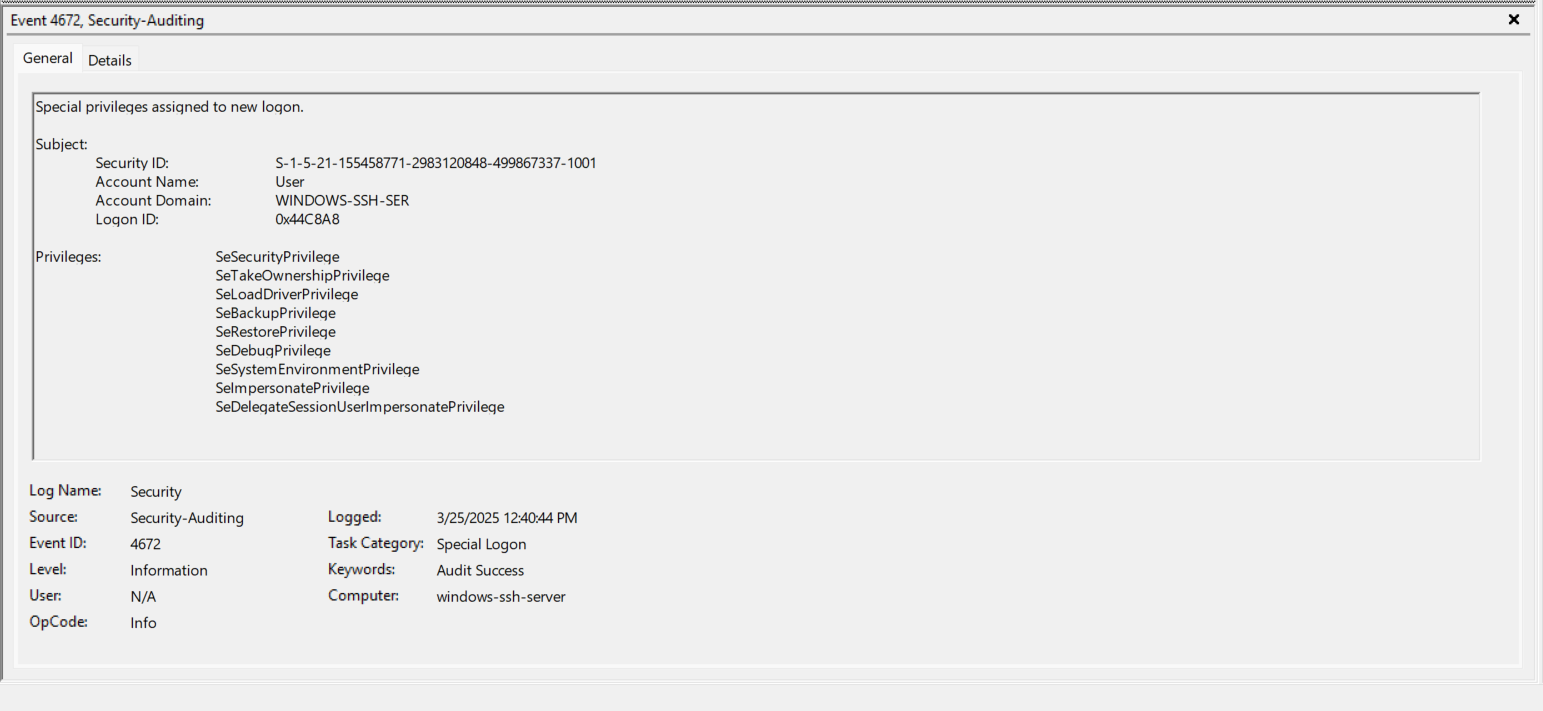

- EventID 4672 (0x44C8A8) - “User” is given a bunch of privileges. Note the Logon ID of 0x44C8A8.

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/it-pro/windows-10/security/threat-protection/auditing/event-4672

- SeSecurityPrivilege - Manage auditing and security log

- SeTakeOwnershipPrivilege - Take ownership of files or other objects

- SeLoadDriverPrivilege - Load and unload device drivers

- SeBackupPrivilege - Back up files and directories

- SeRestorePrivilege - Restore files and directories

- SeDebugPrivilege - Debug programs

- SeSystemEnvironmentPrivilege - Modify firmware environment values

- SeImpersonatePrivilege - Impersonate a client after authentication

- SeDelegateSessionUserImpersonatePrivilege

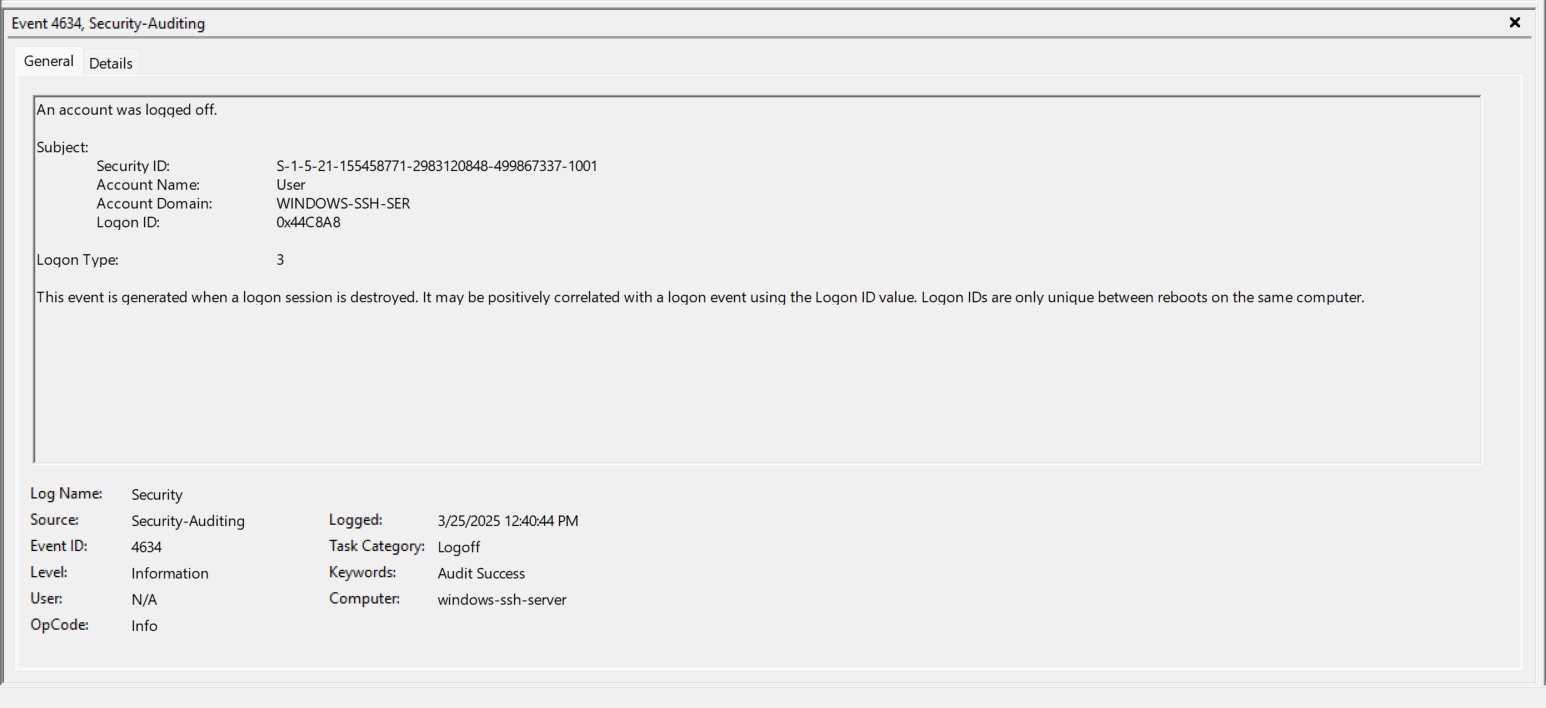

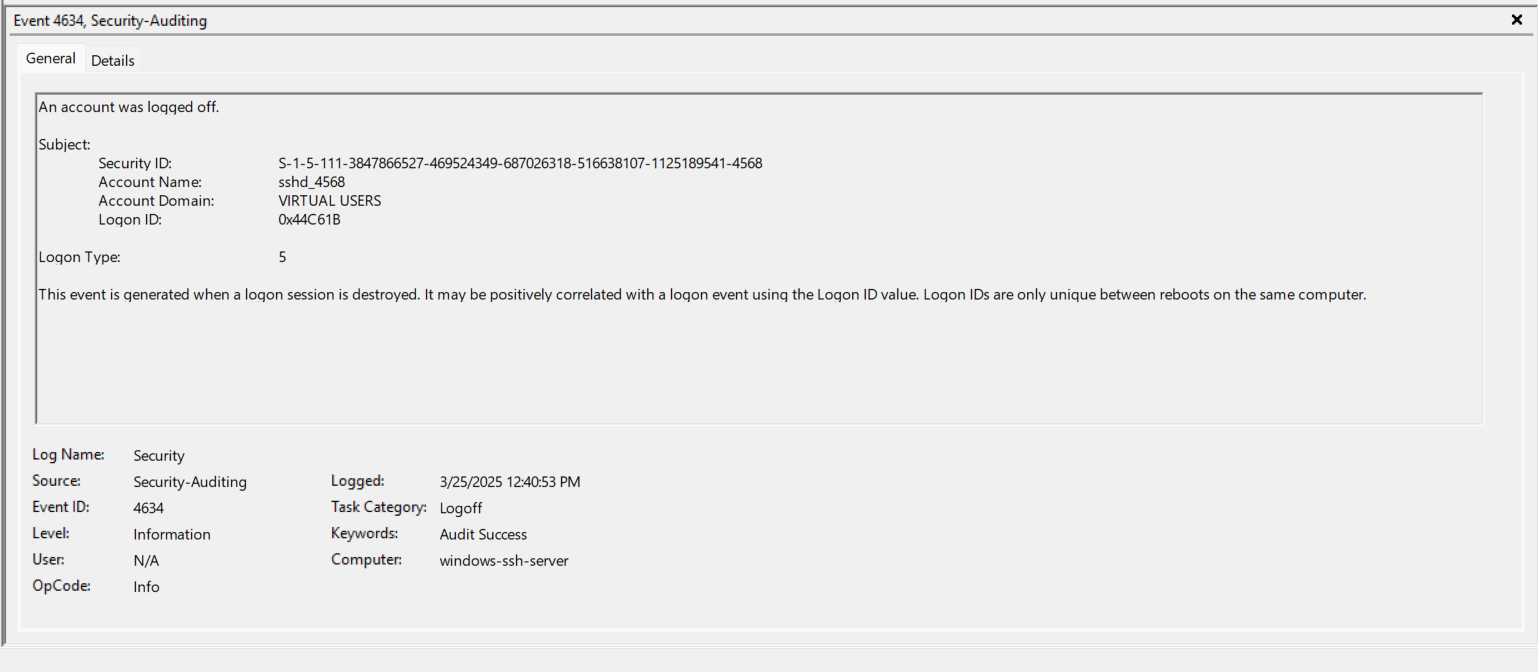

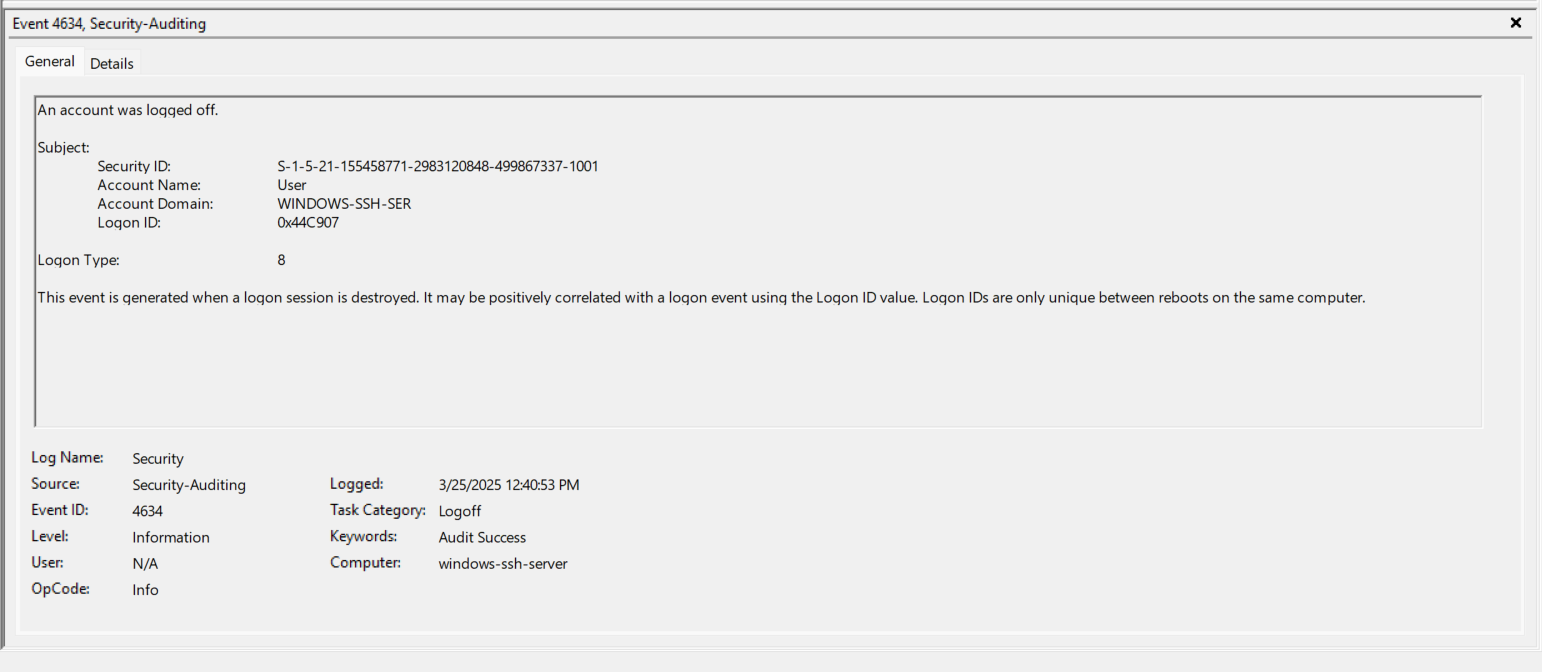

- EventID 4634 (0x44C8A8) - The “User” is now logged out which is interesting because I hadn’t closed the SSH Session yet. Note the Logon ID of 0x44C8A8. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4634

- EventID 4798 (0x3E7) - Repeat of Step 6 above.

- EventID 4648 (0x3E7) - Repeat of Step 7 above.

- EventID 4624 (0x3E7) - Repeat of Step 8 above.

- EventID 4672 (0x44C907) - Repeat of Step 9 above.

- EventID 4634 (0x44C61B) - The “sshd_4568” is now logged out and this correlates with closing the actual SSH Session.

- EventID 4634 (0x44C907) - The “User” is now logged out and this correlates with closing the actual SSH Session.

Failed Login

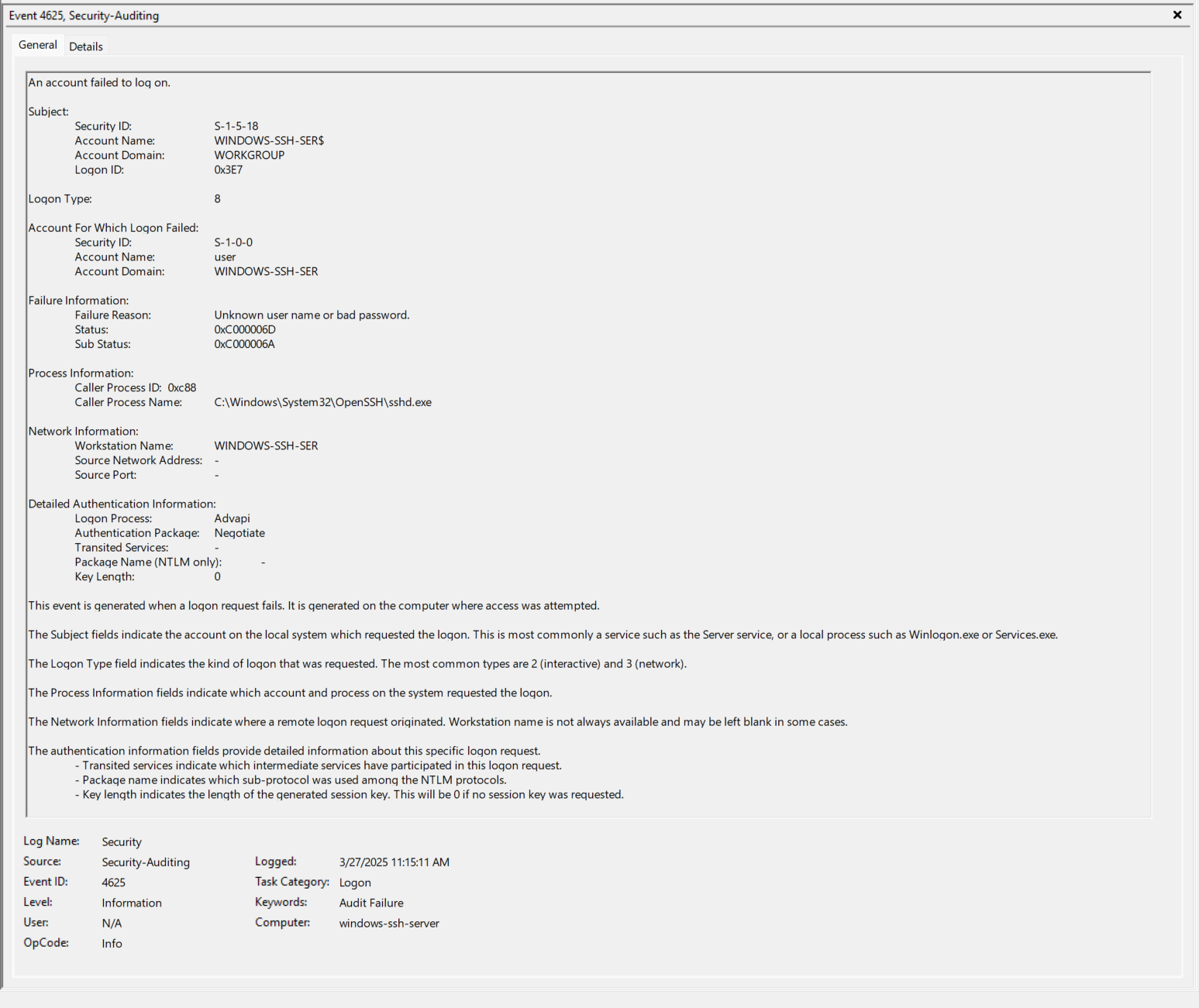

When a user inputs a bad password, the logs are similar for Steps 1 - 10 above. There would be the obvious differences in Logon IDs and the “sshd_####” account.

- EventID 4625 - The “User” account fails to login. https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventid=4625

- EventID 4634 - The “sshd_####” is now logged out and this correlates with closing the actual SSH Session.

Connect No Attempt

When a user connects but makes no attempt to enter a password, the logs are similar for Steps 1 - 10 above. There would be the obvious differences in Logon IDs and the “sshd_####” account.

- EventID 4634 - The “sshd_####” is now logged out and this correlates with closing the actual SSH Session.

SSH Private/Public Key

Unlike Debian, authenticating with keys must be explicitly enabled in Windows. I had to modify the sshd_config file located at C:\ProgramData\ssh\sshd_config to allow connections using a public key. Steps can be found at the following link along with some other details https://woshub.com/connect-to-windows-via-ssh/. One point to note, you can enable local logging to the sshd.log file. Again, this is not enabled by default and instead logs are stored in the Windows Event Logs.

By default the Private/Public keys are stored at %userprofile%\.ssh.

The Windows 11 Server saves the public key in the authorized_keys file located at %userprofile%\.ssh for the relevant user. They could also be stored at C:\ProgramData\ssh\administrators_authorized_keys for system-wide management.

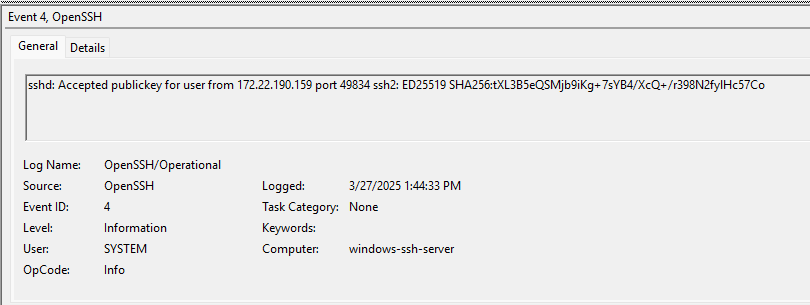

Event Viewer

Under Applications and Services Logs -> OpenSSH -> Operational, we see a record for the successful login using a Public Key.

The Windows Logs -> Security records are no different from the standard username/password authentication.

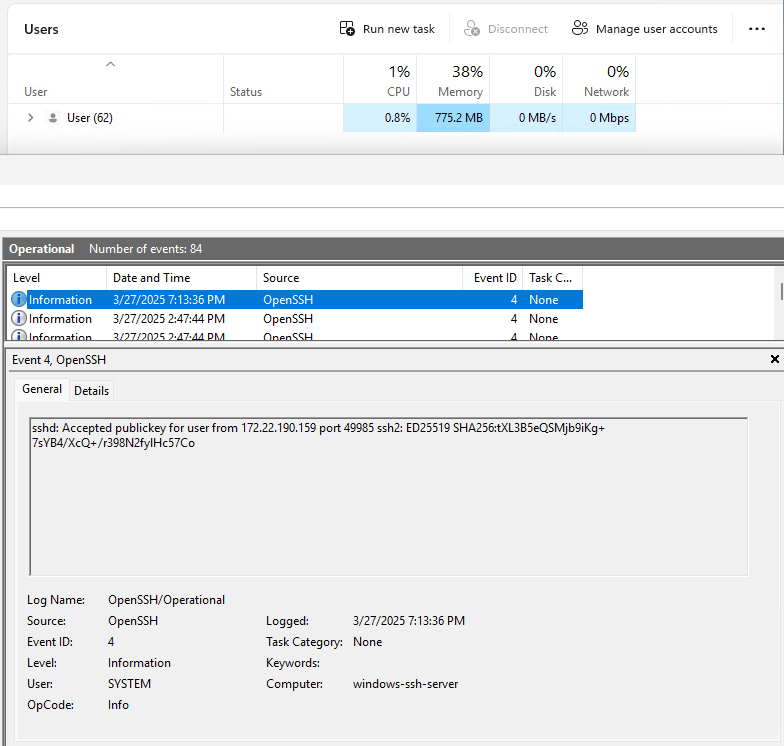

Active Connections - Windows

While an SSH connection is active lets see what is visible. Unlike Debian, the Windows alternative to the who and w command shows us no useful information. By looking at the “Users” tab in Task Manager, we can see all users accounts that are currently logged into the computer. In the screenshot below, we only see the “User” that we logged into the server Windows machine and no “User” account for the SSH connection.

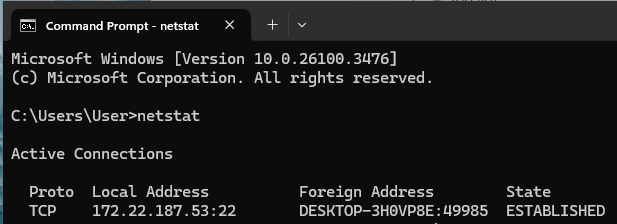

Running netstat shows us the active SSH connection on port 22.

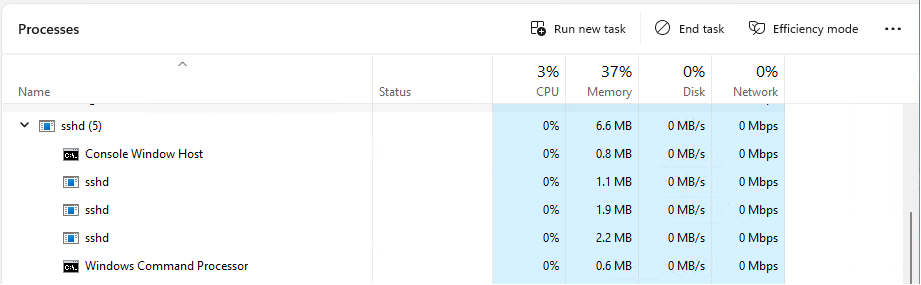

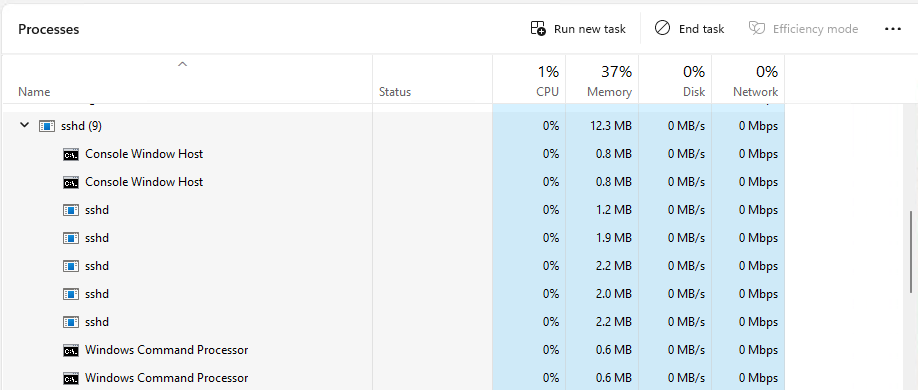

If we look at the “Processes” tab in Task Manager, there is an sshd process and when there is an active SSH connection it will have 4 child processes as in the first screenshot below. One of the sshd processes is the parent one and so for every active SSH connection there will be:

- 1 Console Window Host process

- 2 sshd processes

- 1 Windows Command Processor process

The second screenshot below shows what happens when there are two active SSH connections.

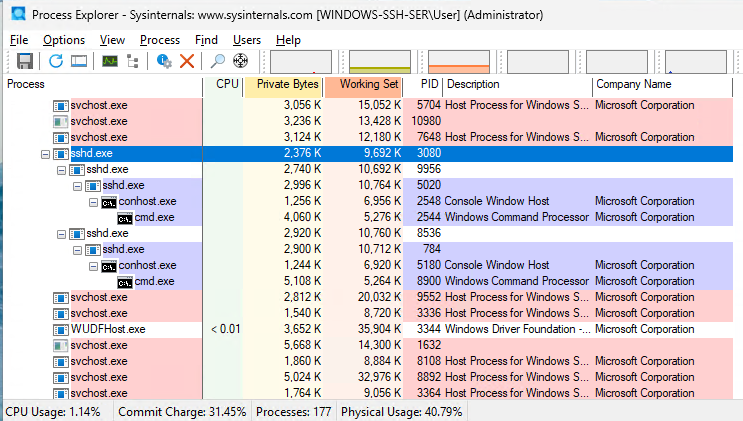

A nicer hierarchical view is given by user Process Explorer.

Conclusion

I ran out of time to do the testing for SSH Tunnels. I have a suspicion that the artifacts would be the similar just like they were for the Debian testing.

For a default installation of Windows 11 the following files/locations could be of interest when trying to track SSH connections:

| File/Location | Server/Client | Notes |

|---|---|---|

%appdata%/Microsoft\Windows\PowerShell\PSReadLine |

Client | Shows history of Powershell commands. Only useful if they used Powershell to initiate the SSH connection |

%userprofile%\.ssh\known_hosts |

Client | Hostnames/IPs of trusted remote hosts. |

| Windows Event Logs | Server | Logs on the server will show details about connections. These can be found at “Applications and Services Logs -> OpenSSH -> Operational” and “Windows Logs -> Security”. Nothing on the client. |

| Private Key | Client | Typically stored at %userprofile%\.ssh. |

| Public Key | Both | Typically stored at %userprofile%\.ssh and possibly C:\ProgramData\ssh\administrators_authorized_keys on the server. |

Assuming the Private key isn’t passphrase protected, having the Private/Public keys are a big boon to any investigation. They would allow the investigator to connect to the remote host.

One interesting note, you can turn on local logging for sshd by editing the C:\ProgramData\ssh\sshd_config file. This will end up writing logs to the C:\ProgramData\ssh\logs\sshd.log file. Something to keep in mind if you are ever investigating SSH as this might be another source of artifacts. I did not test this.

In the moment, the following tools/commands can be useful to investigate SSH connections:

| Tool/Command | Server/Client | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Task Manager/Process Explorer | Both | Shows either the ssh process on a client Windows machine or sshd processes and their children on a server Windows machine. |

| netstat | Both | Shows active network connections and their ports |

References

- https://woshub.com/connect-to-windows-via-ssh/

- https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/it-pro/windows-10/security/threat-protection/auditing/event-4672

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/it-pro/windows-10/security/threat-protection/security-policy-settings/log-on-as-a-service